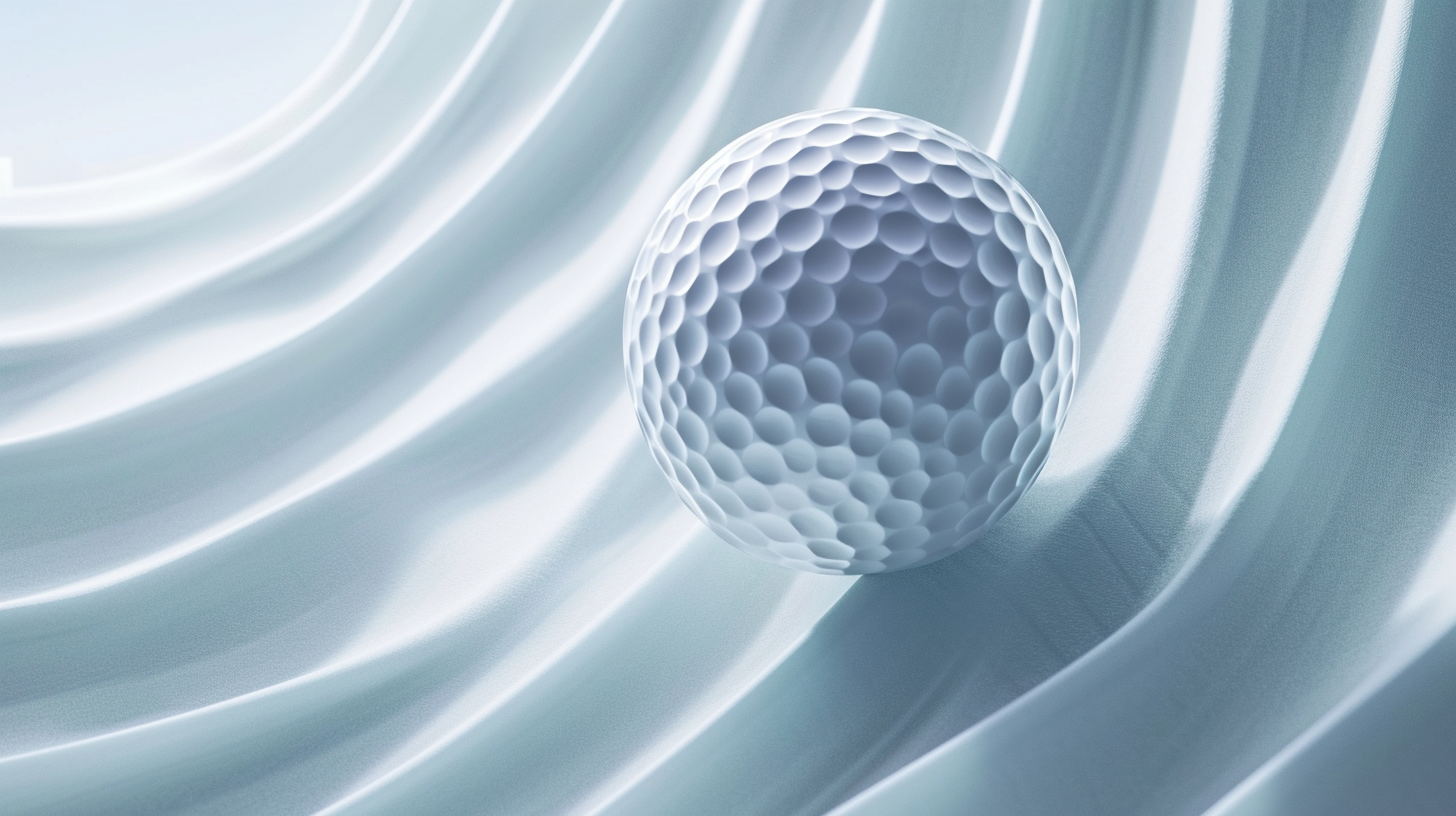

Ever wonder about those little dimples etched all over your golf balls and what they actually do?

As it turns out, these numerous tiny holes serve an important aerodynamic purpose critical for a properly hit shot.

Read on as we dive into understanding more about dimples, including how many dimples are on a standard golf ball and why that number matters when it comes to flight performance.

How Many Dimples On A Golf Ball?

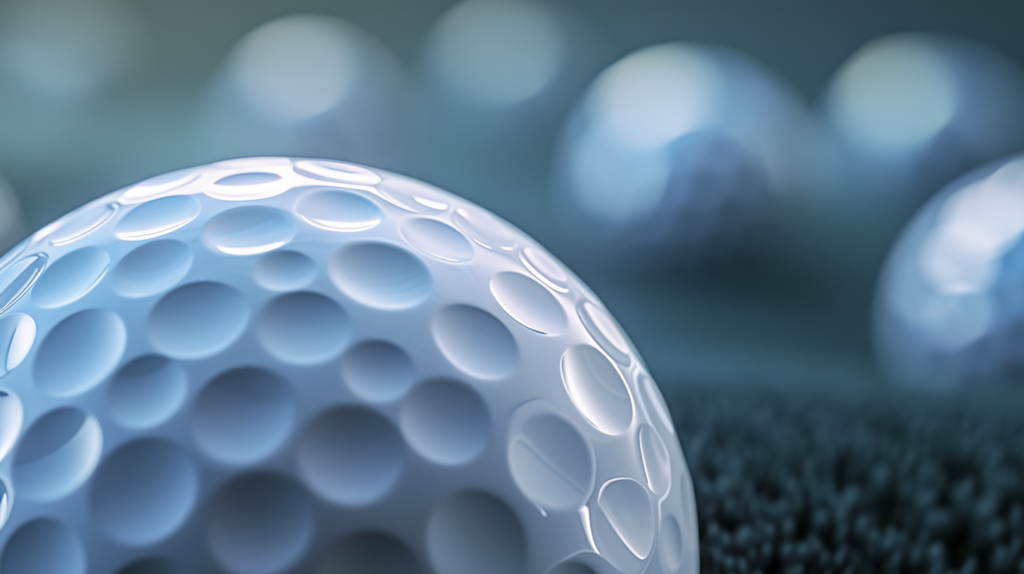

The total number of dimples engraved on the surface of a regulation golf ball ranges from 300 to 500. Most models from top brands feature between 330 to 450 dimples.

Professional level balls used in tournaments and championships adhere to this standard, as golf’s ruling bodies carefully regulate specifications for approved play.

To be more specific, Titleist’s 2023 Pro V1 balls have a dimple count of 352. The Callaway Chrome Soft line features 334 dimples, while Srixon’s Z-Star series has 324.

Bridgestone’s premium Tour B golf balls contain 330 dimples. So while there is some variation between popular options on the market, well-constructed balls from reputable companies all fall within the approved range of 300 to 500 dimples.

What Are Dimples and Why Do Golf Balls Have Them

Golf balls have small circular holes on their surface known as dimples. Dimples are indented areas spread across the exterior of the ball.

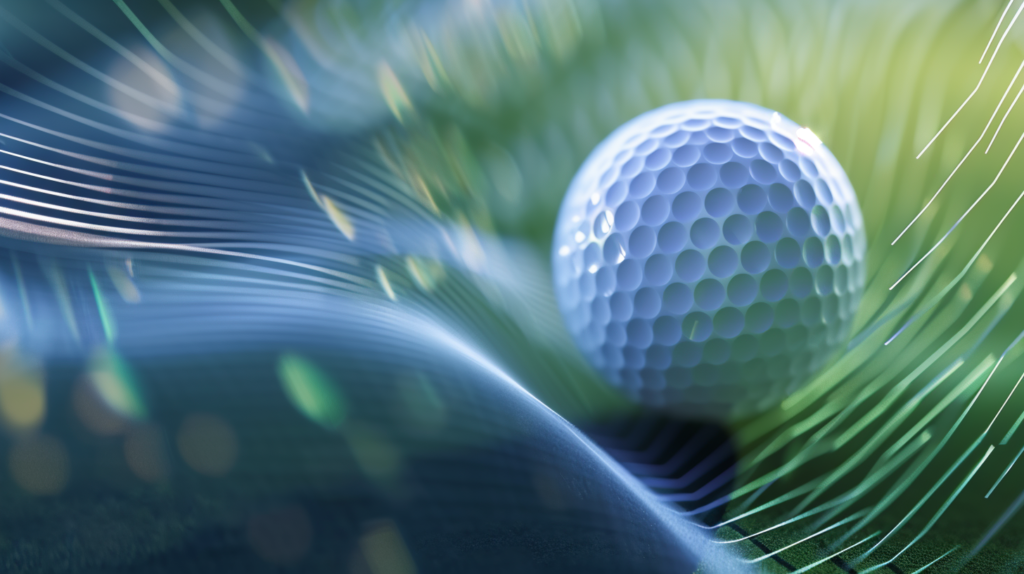

They play an important role in the aerodynamics and flight path of a golf ball. When hit, the streamlined surface formed by the dimples generates lift and allows the ball to carry a farther distance.

The effect occurs from the way the dimples alter airflow around the ball during flight. The circular depressions create a turbulent boundary layer of air that clings to the ball’s surface.

This allows the smoothly flowing air to follow the contour of the ball’s surface for a little longer. As a result, there is less aerodynamic drag working against the golf ball in flight.

Standard Number of Dimples

Most regulation golf balls on the market have between 300 to 500 dimples covering their surface. Typical tour-quality golf balls used in professional tournaments and championships usually have somewhere around 330 to 450 dimples.

A higher dimple count within this range provides the greatest possible surface area and greater lift for longer drives.

Balls with more dimples can typically produce a higher trajectory and increased carry. There is more turbulence created by the dimples to produce enough lift to keep the ball in the air longer.

By optimizing how far and fast a shot travels down the fairway, dimple patterns play a key part in helping golfers strategically position the ball short of the green. However, there is a point of diminishing returns where too many dimples can produce excessive lift that reduces distance.

Regulating bodies put limits on dimple number and arrangements allowed during competitive play.

How Dimples Are Arranged

Rather than being placed randomly across a golf ball’s surface, dimples are carefully positioned in consistent patterns. These symmetrical arrangements maximize the portion of the ball covered by dimples, around 70 to 80 percent of the total surface area.

Distributing dimples uniformly also helps achieve proper spherical symmetry and an aerodynamic profile.

Common layouts position dimples in an orderly fashion using geometric shapes. A popular example is the icosahedron pattern consisting of 20 triangles that form a sphere.

Golf ball companies may also use octahedron shapes with eight triangular faces as a template. When wrapping a 3D shape around the ball, the protruding corners create natural locations for dimple placement.

Additional dimples then fill in the space between the main ones. While the number may vary, companies try to adhere to a repeated motif for quality control and optimal flight performance.

Variations in Dimples

Some brands and ball types feature alternative dimple designs that stray from the typical 300 to 500 count convention. For instance, the Polara golf ball has only about 100 large dimples rather than many tiny ones.

Since dimples reduce drag and increase lift by creating turbulence, the idea is that fewer, larger dimples could improve airflow even further. However, in order to achieve a regulation weight and size, these balls compensate with a denser core material than normal models.

There have also been experiments with golf balls having dimples inside other dimples or with empty rectangles rather than circles.

Various patterns claim incremental advancements, yet none widely deviate enough to significantly outperform and replace the standard layouts used today.

While innovation continues, strict testing from golf’s ruling bodies ensures approved balls adhere to optimal standards.

Impact of Dimple Design on Performance

It is not just about the number of dimples but also their geometric properties that dictate aerodynamic results. Minor aspects like the dimple edge angle, diameter, depth, and distribution pattern all influence lift, drag, and trajectory.

For instance, steeper dimple edges strengthen turbulent interaction. The orientation and spacing of dimples alter how smoothly air flows to produce lift.

Companies constantly tweak dimple specifications through simulations and experiments searching for the best combination. Advancements in computer modeling and wind tunnel tests reveal nuanced performance gains from subtle dimple formula adjustments.

With such fine margins determining an errant slice or pure strike, every detail aims to produce the intended flight of the shot. Testing also validates manufacturing consistency so the same input yields the same carrying capability.

Through small changes in dimple design parameters, engineers can further optimize launch angle, peak height, descent angle, carry distance, and aerodynamic forgiveness.

As limitations narrow closer to the theoretical ideal dimple pattern, companies leverage proprietary dimple specifications to distinguish their golf ball offerings.

Tiny dimple modifications with supported testing helps market innovations and advances in competitive technology.

What Are Dimples and Why Do Golf Balls Have Them

Golf balls have small circular holes on their surface known as dimples. Dimples are indented areas spread across the exterior of the ball.

They play an important role in the aerodynamics and flight path of a golf ball. When hit, the streamlined surface formed by the dimples generates lift and allows the ball to carry a farther distance.

The effect occurs from the way the dimples alter airflow around the ball during flight. The circular depressions create a turbulent boundary layer of air that clings to the ball’s surface.

This allows the smoothly flowing air to follow the contour of the ball’s surface for a little longer. As a result, there is less aerodynamic drag working against the golf ball in flight.

Standard Number of Dimples

Most regulation golf balls on the market have between 300 to 500 dimples covering their surface. Typical tour-quality golf balls used in professional tournaments and championships usually have somewhere around 330 to 450 dimples.

A higher dimple count within this range provides the greatest possible surface area and greater lift for longer drives.

Balls with more dimples can typically produce a higher trajectory and increased carry. There is more turbulence created by the dimples to produce enough lift to keep the ball in the air longer.

By optimizing how far and fast a shot travels down the fairway, dimple patterns play a key part in helping golfers strategically position the ball short of the green. However, there is a point of diminishing returns where too many dimples can produce excessive lift that reduces distance.

Regulating bodies put limits on dimple number and arrangements allowed during competitive play.

How Dimples Are Arranged

Rather than being placed randomly across a golf ball’s surface, dimples are carefully positioned in consistent patterns. These symmetrical arrangements maximize the portion of the ball covered by dimples, around 70 to 80 percent of the total surface area.

Distributing dimples uniformly also helps achieve proper spherical symmetry and an aerodynamic profile.

Common layouts position dimples in an orderly fashion using geometric shapes. A popular example is the icosahedron pattern consisting of 20 triangles that form a sphere.

Golf ball companies may also use octahedron shapes with eight triangular faces as a template. When wrapping a 3D shape around the ball, the protruding corners create natural locations for dimple placement.

Additional dimples then fill in the space between the main ones. While the number may vary, companies try to adhere to a repeated motif for quality control and optimal flight performance.

Variations in Dimples

Some brands and ball types feature alternative dimple designs that stray from the typical 300 to 500 count convention. For instance, the Polara golf ball has only about 100 large dimples rather than many tiny ones.

Since dimples reduce drag and increase lift by creating turbulence, the idea is that fewer, larger dimples could improve airflow even further. However, in order to achieve a regulation weight and size, these balls compensate with a denser core material than normal models.

There have also been experiments with golf balls having dimples inside other dimples or with empty rectangles rather than circles.

Various patterns claim incremental advancements, yet none widely deviate enough to significantly outperform and replace the standard layouts used today.

While innovation continues, strict testing from golf’s ruling bodies ensures approved balls adhere to optimal standards.

Impact of Dimple Design on Performance

It is not just about the number of dimples but also their geometric properties that dictate aerodynamic results. Minor aspects like the dimple edge angle, diameter, depth, and distribution pattern all influence lift, drag, and trajectory.

For instance, steeper dimple edges strengthen turbulent interaction. The orientation and spacing of dimples alter how smoothly air flows to produce lift.

Companies constantly tweak dimple specifications through simulations and experiments searching for the best combination. Advancements in computer modeling and wind tunnel tests reveal nuanced performance gains from subtle dimple formula adjustments.

With such fine margins determining an errant slice or pure strike, every detail aims to produce the intended flight of the shot. Testing also validates manufacturing consistency so the same input yields the same carrying capability.

Through small changes in dimple design parameters, engineers can further optimize launch angle, peak height, descent angle, carry distance, and aerodynamic forgiveness.

As limitations narrow closer to the theoretical ideal dimple pattern, companies leverage proprietary dimple specifications to distinguish their golf ball offerings.

Tiny dimple modifications with supported testing helps market innovations and advances in competitive technology.

Conclusion

In the end, the 300 to 500 tiny dimples imprinted on a golf ball may seem insignificant, yet they have a remarkably powerful effect. Their number, patterns, and precise dimensions critically influence the launch, trajectory, carry, and accuracy of a shot.

As aerodynamics push the limits of golf ball flight performance, companies continue fine-tuning proprietary dimple formulas in search of any fractional improvement.

The astoundingly complex aerodynamics engineered into these little dimples exemplify just how much technology goes into propelling a little white ball down the fairway.